The Passing of a Most Famous Triathlete

On August 11, 2014, comedian, actor, and philanthropic -athlete, Robin Williams passed. He was 63 years of age and a damn fine cyclist. While he never competed in the sport of triathlon, Williams was a fan of our three ring circus. Catalyzed by a chance conversation with his personal trainer, Robin and I become friends the best way possible--we rode bikes in the silence of mutual suffering. Some years later my wife, Virginia and I invited him and his family to the finish line of a race "just a mile or so" from his home in San Francisco and introduced him to the triathletes that he might ultimately connect with-- Welchy, Wingnut, Barb and Loren Lindquist—a handful of jocks and jockettes who wouldn't gush and ask and befriend him only in the star-gaze service of their own self. He loved the tri-geeks he would pal with. And they him.

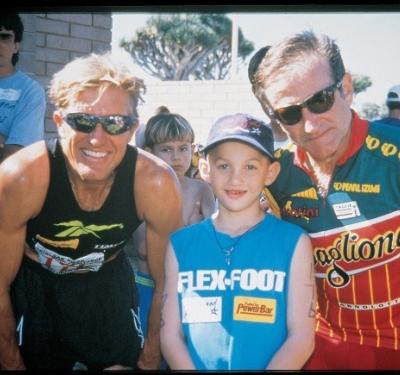

For eight straight years he supported the Challenged Athlete's Foundation's San Diego Triathlon Challenge by posting up at the start, riding the good ride, and sticking around when all the cameras had gone home. Robin had a sensibility to those athletes who lived out on the margins due to accident, injury, and fate. In another life and maybe this one, he'd claim, we are all challenged athletes.

Robin Williams' contributions to the sport can never be quantified as power wattage or BPM. He simply appreciated the wild and crazy side of our sport, however measured or far away.

See more on Robin Williams and triathlon at http://www.scotttinley.com/writtenword.htm

"I think now, looking back, we did not fight the enemy; we fought ourselves. And the enemy was in us. -- From Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen) in Platoon (1986)

I. The Treason of the Artist

In Arthurian legend, the Fisher King is one of a long line of protectors of the Holy Grail. But this King is wounded, emasculated in such a disguised fashion that he continues to protect the Grail but cannot father an heir in his impotence. His weakness, visibly affecting the health and strength of his kingdom, causes him much suffering. But still he protects the Grail, waits for someone to heal him, and fishes at the river.

For Robin Williams, the actor-comedic who opted out of life on 8/11/14, a vital and viral artistic king, depression was his impotence. His choice exposed how the protector role, once again, does nothing unless deeper root problems are exposed.

Pundits have offered thoughts on the intersections of Williams' acting and comedic skills, his mental state, and his profound body of work—over eighty films in three decades. The demons that visited his head, some have voyeuristically-argued, are the catalysts that generated his genius. And while there is little doubt that his amazing wit and intellect, when applied to popular culture references and offered through his intricate impressions...these were the foundations of that manic style of rapid fire comedy.

But, for this friend and fan, it was his dramatic roles that shown the humanness and the spirit of his life. This is where his inner battles were waged. These roles--when the prefect pain comes in contact with the perfect part--are the treason of the artist: Jim Morrison singing The End, Picasso's Starry, Starry Night, Frida Kahlo's The Two Fridas, Lou Gehrig's Luckiest Man in the World speech, Roosevelt's A day that will live in infamy, David Foster Wallace's Infinite Jest. So, when Robin Williams tells Matt Damon's character in the film Good Will Hunting that, "you're a genius, Will. No one denies that. No one could possibly understand the depths of you," we might ask who Williams is speaking to or about.

As fans, we fail to see the pain hiding just behind the devouring eye; we fail to see the associated torment of artistic brilliance. And the artist is always on stage, offering things they must. For they are always and already on the cusp of madness. We just never see it.

Ursula K. Le Guin argues in her seminal work, Those Who Walk Away from Omelas, that "only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting." For the artist trading pointy edges with the pain of addiction, depression, and is-it-all-worth-it questions, these roles act as a kind of release valve for their suffering. And in some odd marriage of production and consumption, the fan consumes the metaphor for their own disparate but connected lives. Thus, Hemingway's foray into the vagaries of the Spanish War function on the same level as Kurt Cobain's lyrics from his song, Downer:

Butchered sincerity, act out of loyalty

Defend your true country, wish away pain

Hand out lobotomies, to save little families

Surrealistic fantasy, bland, boring, pain

The artist's work is a test for what might be a normal life. But the paradox returns when the fan responds with "they were just brilliant in that role." Were they acting, we might ask, or projecting a need to find some essential normalcy?

Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh, Charlie Parker's Ornithology, Robin Williams in The Fisher King wondering why we haven't learned the musical lessons of John Lennon to give peace a chance—these are the brilliance of our artistic composers. But hidden in those performances--whether real or imagined—is what Le Guin calls "the banality of evil, and the terrible boredom of pain." That is the treason few see and fewer feel, buried beneath the rubble of material wealth and immaterial fame.

II. To Be King, Just for a Day

Few of us fully understand the perils of a vaulted existence. Many of the fallen artistic heroes have surrendered wholly to the pursuit of earthly greatness, exposing them to the terrifying process of public ruination when failed morality and the ravages of physical decline or extinguish come to collect. They suffer both in their boot-strapped quests and their ignominious return to regularity. All for the chance to be king. And most say they wouldn't change a thing. When they fail as royalty, they are laid bare on the altar of social media. And suddenly they have ten thousand new best friends who could've saved them.

Celebrities die and the carrion swoop. Copters, cameras, and commercial talking heads stabbing and dodging; the natural commoditization of an (un)natural death sets in motion the fallen hero machine. Life becomes as thin as the green paper that drives the Industrial Celebrity Complex.

"Ah, geez," they suggest. "If only he would've called me. I could've taken him out for a few beers and eased his pain." I never drank with Robin Williams. But I drank for him.

*****

The story of Robin Williams is the story of a man both conflicted and divided; that tormented genius who sought anonymity on a bike or a treadmill or a walk in the woods. Who only wanted to be one-of-the-dudes. On one of our first bike rides we stopped for coffee and some yahoo asked for the Scottish Golf Skit. Give it to us, Robin! The barrister rolling her his eyes and flashing Robin a few Tiburon, CA gang signs.

"It's okay," her fingers signaled, "He's just another 27 year old wonder-geek who sold his start-up app for eight figures."

On the way home, held up at a red light, a dark haired MILF hailed from a minivan, "luv you long time, Robin," and pulled her tube top over her pony tail as the light changed to green and the kids drooled from the 2nd and 3rd row seats.

"Is this the way it works, Robin?" I asked. "You are on stage 24/7?"

"Every day. Every. Fucking. Hour."

"Is it worth it?"

"Can't see that I have a choice. And I'm good. You know? And I love it. Did I say that I'm good?"

"Copy that. Maybe we go west for a few miles. The road less star-stricken."

"Copy that."

"It's good to be king, eh Captan, oh my slow-riding Captain? "

"Fuck off, Tinley."

An essential difference in leadership, regardless of the platform or effect, is in motive. Some kings are effective for their results however managed and attained. Others are successful because they do it for the right reasons. Robin Williams was successful in his roles because they weren't roles. Just extensions of his being. Using not just his fame but the strategy of being famous, Williams effected positive change in many of those who struggled with more obvious bad hands dealt.

In our darkened living room, here's Robin holding the flesh-eaten stumps of a young woman as if they were beautifully manicured hands while the yahoos want to hear him do Mork's nano-nano one more time. Here's Robin defending Lance Armstrong not because he wants to offer an opinion on Armstrong's use of performance enhancing drugs but because he sees Lance as a survivor, as a kid from a fucked up home who beat the cancer bitch. Here's Robin bleeding empathy for the physically-challenged and the cancer- ridden, and the homeless, and the socially beat-to-shit not because they looked like him but because beneath that entire comedic front, there was still the pain. And it was his to negotiate.

III. Suicide and the Hardest Town Played

The country singer, Tom T. Hall, writes about this tenderfoot communion between artists and their followers in his insightful song, Last Hard Town. "They came to see the people that they thought we were and never changed their minds," adding the admission that "what a picker does for others is the thing he's mainly doing for himself" (Hall, 1973). For Robin Williams, his connection to the Everyman, the under-represented, the physically-challenged, and the fallen hero, suggests a response to Hall's argument that no one really knows the celebrity. The fans only know what they want to know.

But watch this boys and girls: Here's the Funny Man marching through cancer wards late at night with nary a camera or PR prop insight. Here's Williams being more than human because this is the best way he knows how to battle the bad hand of depression that he has been dealt. Williams' altruism, while perfectly authentic, just might've carried the additional burden as some disguised plea for help.

Hey folks, I'm doing this because I do care. But I'm also channeling their pain on top of my own. Can't anyone see it? I am the Wounded King who has been tasked with protecting and entertaining those who can't protect and amuse themselves. Does anyone else want this job? Because I just don't know how long I can carry the burden.

And for those who have never felt what David Foster Wallace called "the invisible agony", that ten ton darkness pressing in from all points, this writer pleads compassion for depression, compassion for suicide, compassion for Robin's choice.

As Wallace, who made his own suicidal choice on September 12, 2008 suggests, "Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire's flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors."

If living with depression was the more terrible of Robin Williams' options then I suggest in both respect and humanness, we celebrate the near limitless pleasure he brought millions and find ways of addressing that invisible agony he faced. We celebrate the effects of how he fought the good fight. Because in the wake of those tormented battles came his humanity which is a humanity that is missed. And much needed.

Williams might've thought his race was run, his journey bereft of moral completion. He was no longer vital, his depressed voice might've suggested. His TV series cancelled. Kids through college. Occupational pugmarks checked on the way to banality. But what Robin missed is what most of us miss in our search for redemption. It's what he acted in The Fisher King. Our acceptance of our own fallacies, our own depressions, our own humanness, our own living legacy.

There is one image I have of our times together, of Robin leaning into the pre-teen, physically-challenged lad, Rudy Garcia-Tolson, a boy born without some parts of lower legs and chooses to have the rest simply discarded because, as he would suggest, they just got in the way. Williams looks around the glitterati and the beautiful able-bodied collective at some high-end sporting ceremony and tells the young Garcia-Tolson that it is he, a soulful kid who is more whole than the posturing and pretension abounding.

"Money and legs," I think he said, "over-rated, Rudy. Keep your soul instead."

I don't know what Robin forgot to keep. I just miss my friend.

******

"The war is over for me now, but it will always be there...for what Rhah called possession of my soul. There are times since I've felt like the child born of those two fathers. But, be that as it may, those of us who did make it have an obligation to build again, to teach to others what we know, and to try with what's left of our lives to find goodness and a meaning to this life." -- From Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen) in Platoon (1986)