He had only been a triathlete for a little more than a year, but by 1983 the legend of Mark Allen had already begun to emerge. He was known by his JDavid teammates as “The Grip,” short for “The Grip of Death,” a reference to what it felt like to train with the guy when he was having a good day and you were having… well, a good day too. But as hard as he drove his training partners, he pushed himself even harder, exploring his own physical limitations with intellectual fervor. As a journalist who had covered running and other individual sports for years, I had never encountered an athlete more focused, more curious about his own potential, more philosophical about the process of transcending pain through mental discipline. His raw talent and physiological advantages seemed obvious; it was Mark Allen’s willingness to explore the most daunting corridors of endurance that was already beginning to set him apart.

The Race Tightens

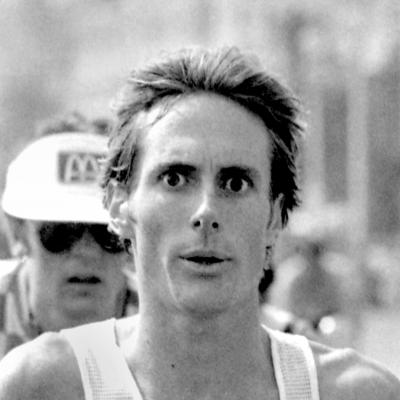

At the long-distance Nice Triathlon in France that year, Allen was defending his 1982 title. The bike course was big and hilly; the run on a hot, sunny afternoon was mostly un-shaded and marked by an unforgivable scarcity of aid stations. Allen led the race with a mile or so to go, and he was moving smoothly down the fashionable Promenade de Anglaise , surrounded by an entourage of media and spectators on bicycles, when his body began to fail. With Dave Scott closing fast behind, Allen went deep inside himself as he began to stagger toward the finish line.

I had been on the course shooting all day. When we arrived back in town, the traffic along the Promenade was terrible. I was behind schedule as it was, and had given up hope of getting to the finish line in time to see Allen, whom I had last seen with a huge lead on Scott, break the tape. But as we approached, I saw a commotion ahead on the wide sidewalk that separated the street from the beach. As we drew parallel, there was Allen, surrounded by bicyclists and cameras. “Stop the car!” I shouted frantically to our driver. “Stop the car!” I scrambled out, the motor drives of my cameras whirring as I went. Allen looked terrible – he was barely running at all – and the outcome of the race, a foregone conclusion only moments before, was now very much in doubt.

Just as I broke through the crowd, Allen’s legs wobbled and he almost fell. We were still shooting film in those days, with manual focus and manual exposure settings, and I was using color stock in one camera for Triathlon magazine and black & white in another, for my own publication, Running & Triathlon News. I was firing away blindly with both pieces of equipment, shooting as I ran, hoping for the best.

I was finally able to position myself on the sidewalk directly in front of Allen, walking backwards as I went, staring through my lenses as he swam through the air in front of him, willing himself forward, his tall, whippet-thin frame widened for balance, all elbows and knees, a parody of his normally smooth, powerful stride. He seemed oblivious to the chaos around him. NBC television commentator and marathon great Frank Shorter, having given up all semblance of journalistic restraint, was screaming encouragement almost in Allen’s ear. A French radio reporter was describing the scene – quite calmly as I recall – from the back of a motorcycle. There were bicyclists, motor scooters, and pedestrians on all sides, pressed close – a tight, frenzied slow-moving caravan, with Allen spotlighted at its center. To this day I have no idea how much of all this Allen was actually aware of. Probably not much. I do know that when I got the shot I wanted, finally sharp, at least passably well exposed in the bright late-afternoon light, Mark Allen was staring right through me, his eyes wide and unblinking, his brain focused on the one place in the world he needed to be: the finish line.